It’s pretty well known that unless you see a grizzly with cubs, its extremely difficult, if impossible, to tell male from female grizzly bears. Recently this was confirmed to me on a trip to Alaska to bear watch. We flew to a small lake contained within the vast wilderness of Lake Clark National Park. The flight took about an hour leaving from Anchorage, landed on the lake, where about fifteen of us boarded pontoons and spent the day circling the lakeshore watching grizzly bears catch salmon.

Because these bears are in hyperphagia and also very used to the boat, we could approach quite close, say fifty feet away while the bears fished. Our boat captain was a veteran with thirteen summers under his belt of guiding and watching these bears. He knew the best spots around the lake where the fishing was good for the bears. And he told us something interesting. When we’d see a single bear (versus a mom with cubs), he had no way of knowing if that bear was a male or female. There was no size comparison to use or any other metric, and he’d been watching these bears for over a decade. In all, we saw over thirty bears in one day.

That brings me to the status of grizzly bears in the Northern Rockies. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Agency is setting the stage to delist the Great Bear next year. Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho are actively pushing for a hunt. The local media is telling stories to encourage a hunt. (“While he doesn’t want grizzlies gone, he thinks hunting them would control their numbers and deter them from attacking people and livestock.”)

If delisting didn’t automatically include hunting, I’d be all in. We delisted bald eagles but don’t hunt them. The narrative around “a hunt” is that grizzly bears will “learn” to stay away from humans, or as the quote above, “control their numbers”.

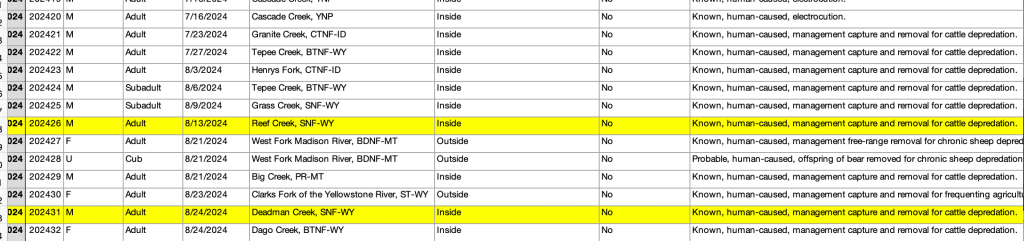

Let’s take the second one first, “control their numbers”. Females don’t begin to have cubs until their 5th or 6th year. Cubs are born in the den the first winter, then stay with mom for 2 more winters. That brings a reproducing female to almost 10 years of age before she can hopefully replicate herself with another female. Grizzlies were the first mammal listed under the ESA in 1975. Fifteen years later, in the mid-80s, most biologists felt they were going to go extinct in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). It took almost fifty years to go from about 200 grizzlies in the GYE to 1000 bears! Every year about fifty grizzlies are killed for a variety of reasons, mostly human caused (euthanized for livestock depredation, killed by hunters, killed by other bears. 53 so far this year 2024). Add a hunt to that and we can very quickly decimate the population once again.

Does killing a solitary animal communicate to other solitary bears to stay away from livestock and human? There’s a sub-adult grizzly that’s been foraging clover this fall in the meadow on the Game Management Area. You can drive your car and watch that bear. If you drive too close, he runs away. But if there’s a hunt, one can legally shoot from a dirt road in Wyoming and he’s certainly close enough, and busy enough foraging, that shooting him would be like shooting fish in a barrel (which is how I see grizzlies in the fall, very absorbed in rooting around because they are in hyperphagia). An easy target for a bear hunter and would killing that sub-adult teach other bears a lesson? Of course not.

Do we need to control grizzly bear numbers? Besides the fact that in the GYE we are already killing over fifty bears a year without a hunt, if GYE grizzlies are to survive long term, they MUST connect naturally with bears in Montana (Northern Rockies). So far they haven’t done this. Wyoming’s plan is to keep killing bears on the edges, the very place where grizzlies must venture in order to connect and foster genetic diversity. Montana’s “plan” is to fly bears into the GYE to maintain genetic diversity, a completely absurd idea!

Anyone who has watched grizzly bears, and any bear biologist will tell you, that these animals are as smart (or smarter) than the Great Apes. They are on par with humans in terms of shear intelligence. Hunting them is simply painful and mean-spirited. Over 100 tribes signed a treaty against a hunt. Grizzly bears are sacred to these tribes. Moving “problem” bears to tribes that want them make more sense. As well as…

- Protect your livestock, feed and garbage

- Most maulings take place in the fall when hunters are prowling quietly through the woods and bears are getting ready for winter. Carry bear spray and if you are not familiar with hiking/hunting in grizzly country, there are plenty of deer and elk all over this country where there are no grizzly bears. What was shocking to me in this article was that these guys had been charged three times over the last several years. I’ve hiked in grizzly country for twenty years and haven’t had an encounter like they described. I don’t know the details of their situation, but it does make me wonder what they are doing wrong.

- I certainly have sympathy for small producers who lose stock to grizzlies on public lands. But public lands are all that our wildlife have and free range cattle should be “at your own risk”, though those risks can be minimized. As noted in my previous post, the ballooning of maximum stock levels on public lands provides a reason for bears to stay low during summer months instead of ranging to higher ground. Are we just feeding these bears with easy prey? There’s been a lot of recent research on non-lethal deterrents. It’s time that the state provides support for that instead of Wildlife Services or direct compensation for losses (grizzly kills in WY are compensated at 3 times the going rate of a cow).

Filed under: New ideas | Tagged: alaska, Bears, grizzly bear, Grizzly bears, Wildlife | 1 Comment »