I was encouraged by The Sierra Club to write an op-ed on the dramatic changes I’ve experienced in my valley since the delisting and hunting of wolves here in Wyoming. With their help, the op-ed came out in The Salt Lake City Tribune.

The original op-ed was a longer more expressive piece which needed to be cut for the Tribune’s size qualification. I thought I’d print that here.

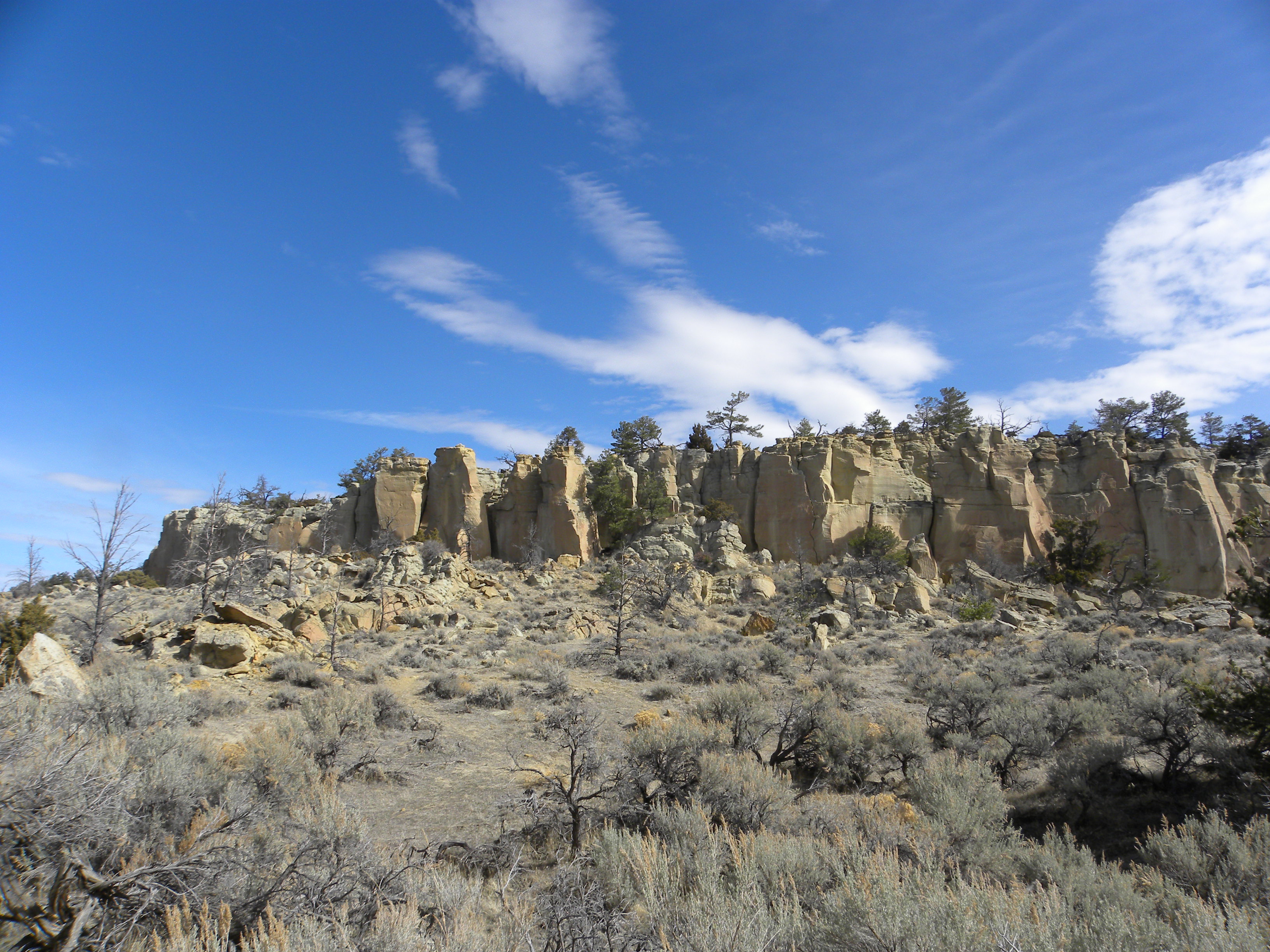

ONE day in late spring when the light is low and dusk lingers for hours, I headed out for a short hike in a series of craggy volcanic contours of hills and narrow arroyos. Some of these gullies hold snow melt run-off for weeks, attracting bears and cougars. Following a narrow animal trail over slippery scree slopes, I slid into a tight channel with a trickle of water running through it to inspect for tracks. As I headed back up the incline to the makeshift trail, a wolf came trotting by. We saw each other simultaneously, less than ten feet apart. I relished the moment, but she didn’t. Startled, she jolted, eyed me for less than a moment, then darted off. This was two years ago and my last close wolf encounter. Although these close encounters are vivid in my memory, my multi-year observations of the impacts wolves had on my valley is the story I cherish most.

I was lucky. I bought a home in a remote valley next to Yellowstone in 2005, less than nine years after the Yellowstone wolf reintroduction. Wolves had been in the valley for a few years, managed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and protected from hunting. Elk descend from the high country starting in December, and the wolves follow the elk. My first resolution was to wake up at dawn at least five days a week during January through March and observe elk, with the hopes of also seeing wolves.

Our coyotes were still learning about living with wolves, many times to their demise. With less coyotes, foxes were making a comeback. Locals told me they hadn’t seen foxes in years. I saw them frequently now. By watching winter bird activity like ravens and magpies, I could find kills. Golden eagles were always there, and surprisingly, bald eagles as well, who winter at lower elevations. The winter landscape was alive and tracking became a favorite activity of mine. Several times I tracked mountain lions to a kill site, only to see where wolves had taken over the cat’s kill. And of course, what a thrill to hear a wolf howl. February, the mating month, I heard wolves howling during the day as well as the early mornings. I saw blood trails during their estrus and my dog sometimes found cached meat under the snow.

At one point, after Idaho and Montana began their wolf hunts in 2009, our area had the highest number of wolves in the Northern Range, over 40 in several packs. I watched as these packs vied for territory, keeping their numbers in check to accommodate for territory and prey. I learned then that wolves self-regulate themselves.

During the spring and summer, when wolves left their pups at rendezvous sites, it wasn’t uncommon to encounter a lone wolf on a hike. I had made sure to have my dog well-trained so he never ran after wildlife, especially wolves. Our valley was alive, and slowly our elk herd was learning how to manage with the return of their ancient predator.

In 2012, the Feds delisted wolves in Wyoming, giving the state jurisdiction. First thing Wyoming did was to begin a hunt which lasted only two years until a Federal judge relisted them. But within those two years wolves developed a fearful relationship with humans. Before that time, watching a wolf pack from the dirt road in a vehicle didn’t bother them; encountering one on a hike, they’d observe you then run away. I never felt threatened by wolves. They are curious by nature, and like most animals, don’t want to have much to do with our species. Yet just a year after that first hunt, if they heard a car coming a mile away in the silent depth of a winter morning, they’d disappear.

From 2014 to 2016, wolves in Wyoming were back on the Endangered Species List. It was an odd interval because even though the Feds now had jurisdiction, they had not planned nor allocated extra resources for this turn of events. During the summer I ran into the USFWS biologist monitoring wolves. He asked me to let him know if I saw any wolves, especially pups. Few wolves were collared and no collaring was going on. The wolves had a short reprieve.

Then in 2017 our wolves were delisted again. Wyoming Game & Fish has decided my hunt zone, adjacent to the Park, is easier for wolf hunting opportunity because of backcountry access. That translates into the highest quotas in the Trophy Management Zone. I’ve asked why we have more harvest success here than other zones. I’m told by game managers that wolf hunters are now coming here just to kill wolves; and there are outfitters specializing in providing that killing opportunity.

With five consecutive years of hunting, I no longer see wolves nor hear them. Our winter nights are strangely silent. Sometimes I catch a few on my trail camera near my house. They always travel at night. There’s no need to look for ravens circling or golden eagles in the winter. Although our recent winters have been mild, dispersing our elk, other friends who hike confirm it’s rare to find kill sites anymore.

One of our wolf pack travels back and forth into the Park with the potential to supply fresh genetics. Last year they did not breed nor did our other main pack. Both were reduced, according to the 2020 report by Wyoming Game & Fish, to just three individuals. This year I was told that same pack was all but wiped out, a pack that has been our stronghold since I arrived in 2005.

Wyoming Game & Fish’s idea of managing wolves is hunting opportunity. But what about my opportunity? The opportunity to hear the primal howl of wolves, to observe them, and to witness all the amazing changes—changes that resulted in a landscape teeming with life. Without the natural play of all the varied wildlife, my valley, like so much of the lower 48, is a bereft landscape.

I am lucky. I’ve had so many unique wildlife encounters, memories I’ll cherish forever. I’d like my children and grandchildren to have those same opportunities. But until state wildlife agencies change their orientation, a posture that considers only hunting opportunity, disregarding ecosystem health and wildlife viewing opportunity, things won’t change. I’m using my sorrow and anger to express what we who cherish our wild lands and wildlife must do–speak up and press for change in state wildlife management outside our National Parks. Perhaps that means relisting wolves and revamping the parameters upon which jurisdiction can be given back to the states. If so, then that’s what must happen.

Until then, I’ll remember those rare and powerful moments I was privileged to experience. One evening while returning home at dusk, three wolves ran across the highway in front of my car. Beginning their night’s hunt, I was struck by their excitement, their intensity and force. They seemed the very embodiment of the immense and wondrous power that is the Universe itself.

Life can be suppressed, but it cannot be crushed. Wolves, in their ceaseless energy, their deep intelligence, epitomize the purity and dynamism of Life itself.

Filed under: New ideas | Tagged: Wolf, wolf hunt, Wolves, Wyoming | 4 Comments »